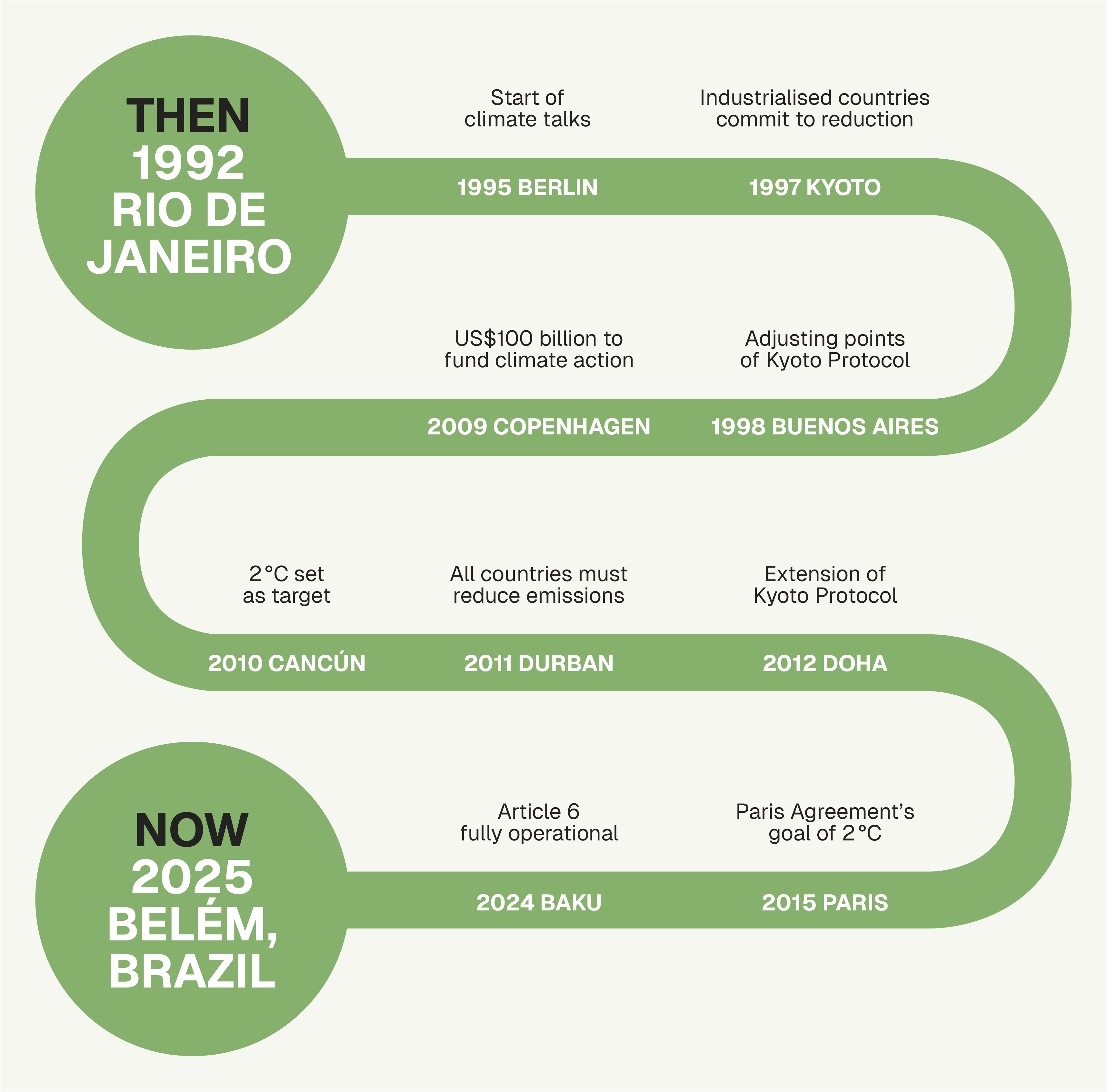

A review of key milestones in previous COP conferences

October 25, 2025Updated 28 October 2025

From 10 to 21 November 2025, the 30th Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC (COP30) will take place in Belém, Brazil. The conference represents the next round of United Nations (UN) negotiations on how to tackle climate change.

For a better understanding of the upcoming climate change negotiations, it’s worth looking at the history of the UN's environmental milestones.

What is the COP?

COP stands for the Conference of the Parties, the UN's annual climate summit. Since 1995, almost every member nation on Earth has come together in a different country each year, except for 2020.

The UN describes the COP as “the supreme decision-making body” of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). It includes representatives of all the countries that are signatories, known as parties, to the UNFCCC. During each COP, the parties review the progress towards the overall goal of the UNFCCC: to tackle climate change.

The world was slow to recognise the urgency of climate change

For a long time, environmental issues like climate change and global warming were not a major concern of the international community or the UN. However, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, a growing environmental consciousness emerged.

In 1972, 23 years after its foundation, the UN organised its first international Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm, Sweden. Known as the first Earth Summit, this conference adopted a declaration that set out 26 principles for the preservation and enhancement of the human environment, agreed upon an action plan containing 109 recommendations, and founded the UN Environment Programme (UNEP).

Since then, the environment has slowly crept up the international agenda. In 1979, the first World Climate Conference (WCC) took place in Geneva, Switzerland. Nine years later, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was formed. Its first assessment report on climate change was released in 1990, and the first meeting of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) was held a year later.

Nevertheless, it took more than 20 years for the international community to commit to action, at the Earth Summit in 1992 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The resulting UNFCCC entered into force two years later, providing a framework for ongoing climate negotiations in the form of preparatory conferences and the annual COP.

The first legally binding agreement on climate change

In 1995, the first Conference of the Parties took place in Berlin, followed by COP2 in Geneva, Switzerland. Both formed the basis for subsequent international climate talks. In 1997, the focus was the implementation of the UNFCCC. After long negotiations, the Parties agreed on the Kyoto Protocol, the most far-reaching climate agreement to date. For the first time, an absolute and legally binding limit on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions for industrialised countries was anchored in an international treaty.

The Kyoto Protocol was ratified by 191 nations several years later on 16 February 2005. Notably, the US was not among this group, despite becoming a signatory during COP4.

With the Kyoto Protocol, 37 industrialised countries committed themselves to reduce GHG emissions to 5.2% below 1990 levels between 2008 and 2012. No restrictions were imposed on developing countries, even high polluters. International emissions trading was also introduced.

Long negotiations lead to a turning point

Soon after the initial negotiations, it became clear that many points of the Kyoto Protocol were still unresolved. For this reason, the parties agreed in 1998 to adopt the Buenos Aires Action Plan, establishing deadlines for finalising work on the different Kyoto mechanisms (Joint implementation, Emissions trading, and the Clean Development Mechanism), compliance issues, and policies and measures. These topics remained the focus for the next decade.

In 2009, COP15 attempted to establish a successor agreement to the Kyoto Protocol, which was due to expire in 2012. Instead, the conference ended with the Copenhagen Accord, which promoted taking action to keep temperature increases below 2°C but did not specify measures.

As well as the non-binding Accord, COP15 did reach three key outcomes. Industrialised countries committing to economy-wide emissions reduction targets by 2020, while countries in the global south committed to voluntary self-financed climate action measures and to establish a register for measures supported by industrialised countries.

Industrialised countries further agreed to mobilise US$100 billion annually by 2020 to fund climate action in countries of the global south, on the condition that the latter make meaningful and transparent mitigation commitments to reduce GHG emissions.

Finally, the conference successfully concluded the two-year negotiations on the rules for afforestation and reforestation projects in developing countries. This resolved the last gap in the Kyoto Protocol's rules of implementation.

Cancún Agreements set the 2 °C global temperature target

At COP16 in 2010, the parties adopted the Cancún Agreements, formalising the 2 °C target of reducing global warming above pre-industrial levels.

The following year, COP17's Durban Platform for Enhanced Action committed all major economies to emissions reduction. The Kyoto Protocol was extended for a second period from the beginning of 2013, which was prolonged to 2020 as part of COP18's Doha Climate Gateway.

COP19 in Warsaw resulted in a road map for a new climate agreement. The Parties also agreed on a rulebook for reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation and a Green Climate Fund for financing mitigation and adaptation measures. COP20 in Lima was the last year of negotiations on the new agreement, which was finally adopted in 2015.

The Paris Agreement: a historic breakthrough

After many years of intensive negotiations, the 196 parties present at COP21 in Paris adopted the Paris Agreement, a legally binding treaty on climate change that mapped out a vision for a net zero emissions future. All countries agreed to submit their climate action plans, known as nationally determined contributions (NDCs), by 2020. All major emitting countries committed to reducing their GHG emissions and strengthening their commitments over time. But the Paris Agreement is perhaps most memorable for its target of limiting global warming to well below 2°C, ideally 1.5°C, above pre-industrial levels.

Climate action at COP following Paris

Germany presented its Climate Action Plan 2050 the following year in Morocco. This was the first country to demonstrate an ambitious long-term climate action strategy, aiming to reduce its emissions by 80% to 95% by 2050. The focus of the following conferences remained on the Paris Rulebook, which addresses questions such as how countries are to measure and report on their GHG emissions.

COP26, which was pushed back to 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, resulted in the signing of the Glasgow Climate Pact. This Pact finally agreed on the Paris Rulebook, and included commitments to end "inefficient" fossil fuel subsidies and to move away from coal.

Perhaps the most important outcome of COP27 in Egypt was the agreement on a compensation fund for the countries most affected by climate change. Additionally, as set out in the Paris Agreement, climate targets will be renegotiated as part of the Global Stocktake.

The final agreement at COP28 in the United Arab Emirates made history by explicitly referencing fossil fuels for the first time in a COP outcome document. The text called for "transitioning away from fossil fuels," a phrase that was widely seen as a compromise. Many climate-vulnerable countries and civil society groups criticised the wording for avoiding stronger language such as "phase-out," arguing that it lacked the urgency and clarity needed to drive meaningful change. Despite this, the reference marked a symbolic shift in global climate negotiations, acknowledging the central role of fossil fuels in the climate crisis.

COP28 also marked the conclusion of the first Global Stocktake, which assessed collective progress toward achieving the Agreement’s goals, revealing that current efforts remain insufficient to limit global warming to 1.5°C. The findings are intended to inform the next round of nationally determined contributions (NDCs), which countries are expected to submit ahead of COP30. The Stocktake underscored the need for accelerated action across all sectors and highlighted gaps in implementation, finance, and ambition.

COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, delivered two major outcomes that advanced the implementation of the Paris Agreement. First, parties agreed on a New Collective Quantified Goal for climate finance, setting a global target of 1.3 trillion US dollars per year by 2035. Developed countries committed to mobilising 300 billion US dollars annually as part of this goal, replacing the previous 100 billion US dollar target set at COP15 in Copenhagen.

However, this figure was met with criticism from developing nations and climate finance experts, who argued that 300 billion US dollars falls far short of the actual needs for adaptation and mitigation in vulnerable regions.

Second, COP29 marked the full operationalisation of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, which enables international cooperation through carbon markets and non-market approaches. Article 6 consists of three components:

- Article 6.2 establishes a decentralised framework for bilateral and multilateral trading of carbon credits, known as Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOs).

- Article 6.4 sets up a centralised UN-supervised carbon market, the Paris Agreement Credit Mechanism (PACM), which is expected to begin issuing credits by 2025 to 2026.

- Article 6.8 focuses on non-market approaches that promote sustainable development and poverty eradication.

Together, these outcomes strengthen both the financial and cooperative pillars of global climate governance, though concerns remain about the adequacy and equity of the commitments made.

COP30 expectations and themes

COP30, held in the gateway city to the Amazon, Belém, is expected to be an important conference to implement many of the ambitions set out in previous COPs. Countries are expected to submit their NDCs ahead of the conference, which will determine each Parties' intentions for realising the Paris Agreement goal. And continuining from recent years, finance and adaptation are expected to be major themes at the Brazilian COP.

Like every year, COP30 is expected to be a key conference in determining the future of climate action, especially as the ten-year anniversary of Paris and its symbolic location in the Amazon.